Angola

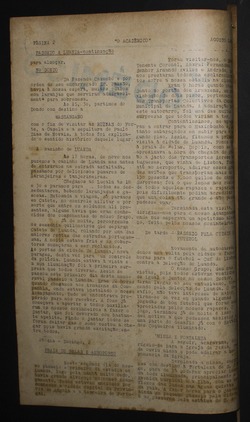

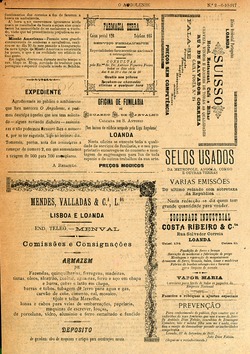

No governo de Pedro Alexandrino da Cunha, em 13 de Setembro de 1845, foi publicado o primeiro número do Boletim do Governo Geral da Província de Angola. Alguns anos mais tarde, em 1856 deu-se a primeira iniciativa de imprensa não-oficial, com a publicação em Luanda de A Aurora, fundado por funcionários públicos, militares e advogados. No entanto, a imprensa noticiosa e independente concretizou-se em 1866, com A Civilisação de África Portuguesa, Semanário dedicado a tratar dos interesses administrativos, económicos, mercantis, agrícolas e industriais da África portuguesa, particularmente de Angola e S. Thomé.

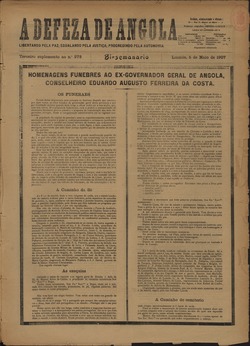

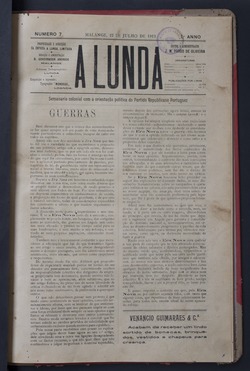

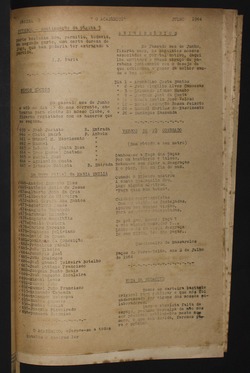

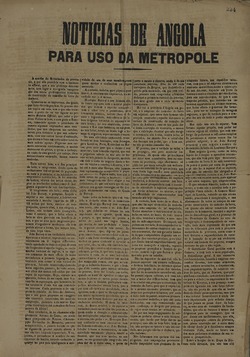

O avanço do projecto colonial português, a desestruturação das sociedades africanas no interior e o enfraquecimento das elites afro-lusas dos centros urbanos contribuíram para o aumento das contradições entre os europeus e os africanos. Neste cenário, ao longo das décadas de 1880-90 fortaleceu-se uma imprensa africana que defendeu a república, advogou a independência de Angola, lutou pelos direitos dos africanos e pela sua igualdade de estatuto em relação aos europeus. No entanto, a perseguição do governo aos jornais e aos jornalistas, em especial aos periódicos de propriedade de africanos, levou ao enfraquecimento da imprensa e a desestruturação de muitos periódicos ao longo da década de 1890.

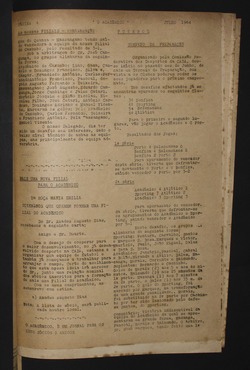

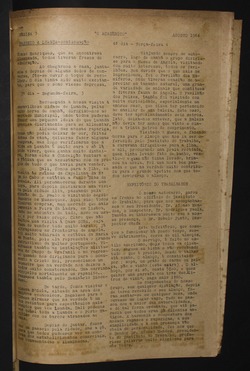

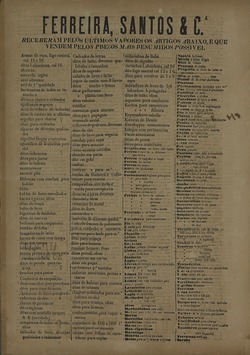

Ao longo do período republicano, a imprensa nativa perdeu o seu protagonismo, devido também aos conflitos entre os ‘filhos do país' e as elites europeias. De facto, a imprensa veio a traduzir os projectos e os conflitos dos grupos coloniais em Angola. A efemeridade dos títulos continuou a marcar o sector, justificada, pelos próprios periódicos, pelas dificuldades económicas e pelas pressões políticas, em especial do governo. Contudo, em simultâneo, surgiram títulos que se afirmaram e que iriam manter-se até 1974. Também se sublinha a continuidade da regionalização, com a criação de novos títulos e a consolidação da imprensa em Benguela, Moçâmedes e Malange

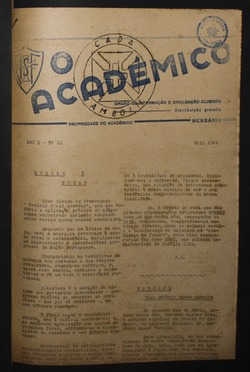

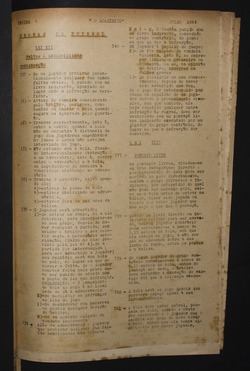

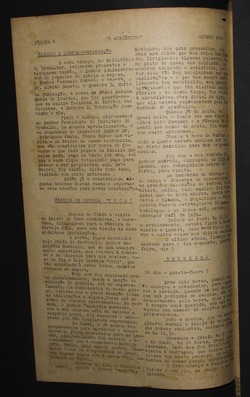

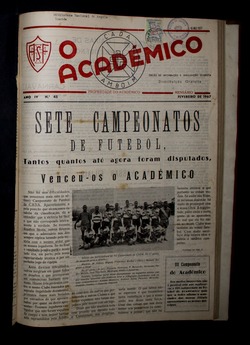

Com a ditadura e a emergência do Estado Novo, a imprensa de Angola foi condicionada pela censura, tendo-se alinhado às directrizes do regime autoritário. Tanto em Luanda quanto no interior da colónia, foram publicados inúmeros títulos, os quais incluíam informação, opinião e entretenimento. Se houve uma imprensa que fez uma crítica moderada às directrizes centralizadoras e proteccionistas do Estado Novo, esta conviveu com uma imprensa que apoiava o projecto político e colonial de Salazar. Assinala-se que a população africana desapareceu da agenda e dos conteúdos jornalísticos ao longo do período autoritário.

Os governos, metropolitanos, gerais e locais, foram decisivos na agenda jornalística, visto que os conteúdos políticos reportaram directrizes, planos, discursos e acções destes, sem questionamento ou crítica, e, na maioria das vezes de forma efusiva. A propriedade dos jornais, associada aos grupos económicos que apoiavam o regime, também foi uma forma do Estado intervir na imprensa.

During the government of Pedro Alexandrino da Cunha, on the 13th September 1845, it was published the first number of Boletim do Governo Geral da Província de Angola (Report of the General Government of the Province of Angola). Some years later, in 1856, the first non-official press initiative happened with the publication of A Aurora (The Dawn) in Luanda, founded by public administration workers, members of the military and lawyers. However, the news and independent press came to light in 1866 with A Civilisação de África Portuguesa, Semanário dedicado a tratar dos interesses administrativos, económicos, mercantis, agrícolas e industriais da África portuguesa, particularmente de Angola e S. Thomé (The Civilization of Portuguese Africa, a weekly newspaper dedicated to administrative, economic, commercial, agricultural and industrial interests of Portuguese Africa, particularly Angola and S. Tomé).

The progress of the Portuguese colonial project, the deconstruction of African societies inland and the weakening of the Afro-Portuguese elite in the urban centres have contributed to the rise of contradictions between Europeans and Africans. In such set, in 1880-90 the African press got stronger: it defended the Republic, it battled for the independence of Angola, and fought for the rights of African peoples and for their equality in relation to Europeans. However, the Government pursuit to newspapers and journalists, especially towards the newspapers which were property of Africans, led to the weakening of press and the dismantlement of many newspapers and magazines during those years.

During the Republican period, the native press also lost its protagonism due to conflicts between the "sons of the country" and the European elite. In fact, the press mirrored these conflicts and the projects of the colonial groups in Angola. There were lesser and lesser publications though, which deeply marked the sector, which was justified by financial difficulties and political pressures, especially from the government. There appeared, however, publications which assured their position until 1974. Also, one must stress the continuity of regionalization, with the creation of new titles and the press consolidation in Benguela, Moçâmedes and Malange.

With the dictatorship and the New State emergence, the censorship regulated the press of Angola making it follow the dictates of the authoritarian regime. Many publications came to light in Luanda and the inland regions, which included information, opinion and entertainment. If there was a press that moderately criticised the New State centralised laws and protectionist dictates, it also had to cohabit with the other type of press – the one which supported the political project of Salazar. One should not forget that the African population disappeared from the journalistic content during the dictatorship.

The governments, be it urban, general or local ones, were decisive in the journalistic agenda, because the political contents reported directives, plans, speeches and actions without any questioning or criticism and, most of the times, effusively. The propriety upon newspapers, linked to economical groups that supported the regime, was also a means of State intervention within the press.